It comes as a surprise to many that the grass beneath our feet is the UK’s biggest crop. The temperate climate, both warm and wet relative to other parts of the world, makes it the ideal environment for growing the green stuff, and especially so in the mild south west. It’s a fantastic free crop that is the keystone of sustainable, regenerative farming when managed sensitively, reducing reliance on environmentally damaging artificial fertilisers, and providing livestock with crucial nutrients through a natural diet.

Yet the industrialisation of farming has not left grass untouched. Perennial rye grass (Lolium perenne) is one of the most highly bred grass species, and is the most commonly found “productive” (ie. actively sown to fulfil a requirement) type of grass grown in this country. Farmers can choose to sow varieties depending on their needs, such as leafy types for deep, lush grazing pastures, or more upright, stemmed plants that co-operate with harvesting machinery. This is especially important when they need to make hay or silage (essentially pickled grass) to feed livestock over the winter when the grass no longer grows.

One thing that all perennial rye grass has in common is how much it loves artificial fertiliser. As a relatively shallow-rooted grass species, it rapidly absorbs the nitrogen released on the soil surface and produces lush growth, so farmers get a greater yield per hectare – ideal when they are feeding large herds as is increasingly common, especially in dairy farming. It becomes a game of numbers both in terms of cows, and tonnes of grass harvested. However, as the rapid growth of perennial rye grass allows it to out-compete other species, this remarkable productivity comes at a cost - the loss of natural biodiversity within the grassland itself. As the types of grass present in a pasture affect the animals who eat it as well as the wildlife who live in and around it, the importance of regarding grass with a little more reverence becomes clear.

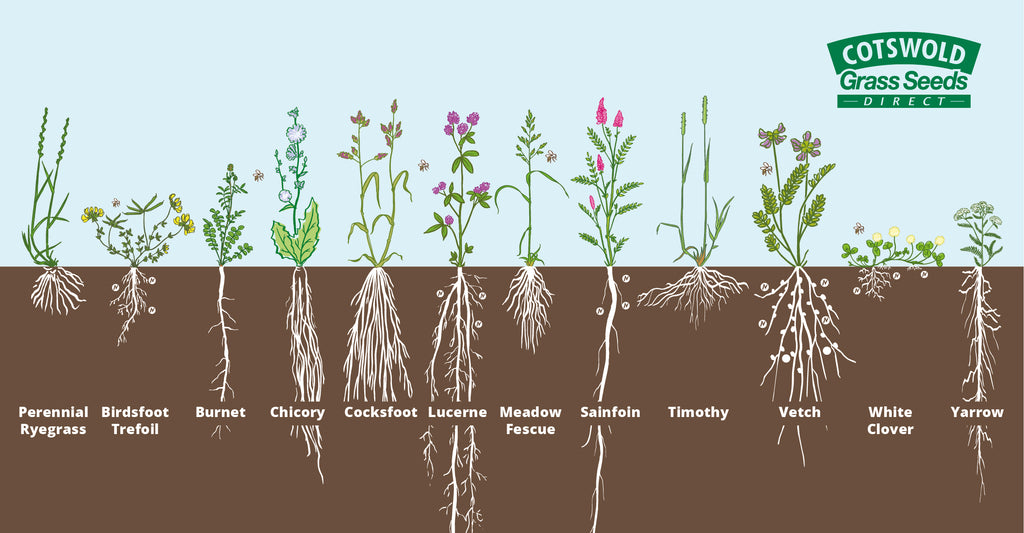

At Pipers Farm we take a more holistic approach to feeding our livestock, with a focus on creating more biodiversity through using ‘herbal leys’ as part of our grazing systems. These are fields purposely sown with a mixture of grass species, herbs and legumes with pleasing names such as Timothy, Yarrow, Birdsfoot Trefoil, Burnet and Cocksfoot. Poetic nomenclature aside, these largely native plants are used to improve both soil structure and the nutritional quality of the sward (the wonderful name for the grassy depths of a pasture) through their deep-rooting nature. Unlike their shallow cousin perennial rye grass they go far deeper into the soil profile, and draw up minerals and nutrients that are crucial for ruminant animals, as demonstrated by the brilliant infographic below, courtesy of our expert friends at Cotswold Grass Seeds. The deep root systems also make the grassland more drought resistant which in turn protects the precious soil beneath. Perennial rye grass should not be demonised completely however; in the right balance it’s a very useful part of sustainable farming. We believe it should not be sown exclusively for its productivity, which comes at the cost of wildlife diversity and the intricately connected gut health of the livestock it supports.

Herbal leys also include plenty of red and white clover, and often other ‘leguminous’ plants such as Vetch, Lucerne and Sainfoin (literally ‘healthy hay’ in French). The pocket of botanical evolution responsible for this family of plants is incredibly valuable to farmers, as legumes bring fertility to the soil naturally. They take nitrogen from the air and ‘fix’ it into their own systems through a symbiotic relationship with the bacteria around their roots. This is another reason why we rear our livestock as naturally as possible; we believe that if we mess with the soil by adding artificial fertiliser, then we mess with the soil biota and how the fungal and bacterial micro-organisms interact with the rhizosphere. This magical-sounding place is the narrow zone of soil immediately around the root – it is literally another world of ecological complexity that soil scientists are still trying to fully understand. Read this scientific paper on root exudates from the Journal of Plant Physiology if you’d like a bit of a geek-out on it. It’s fascinating.

It takes longer to build up soil fertility by using herbal leys, but partnered with rotational cropping it removes the need for environmentally damaging ammonium nitrate fertilisers, which take a staggering amount of energy to produce and rely on finite, mined raw materials.

As with our approach to rearing meat, we take the long view when it comes to managing the fertility of our pastures; the slower, more natural route is the best. Pipers Farm meat is 100% truly grass fed, and never given cereals or concentrates (highly processed energy-packed pellets made from grains, oils, and often soy) as is common practice in standard beef farming systems. Some of our herds also roam on the moors of the south west, where we often see them seeking out a diversity of plants to feed on.

The health benefits of grass-fed beef are known to many, including higher levels of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids and CLAs (conjugated linoleic acids) than are found in beef from grain-fed animals. Catch up on the benefits in this journal post if you are not familiar. Yet not all grass is the same, not by any stretch. We believe that it’s the herbal ley grazing system, while over 100 years old, which offers the best future for sustainably produced beef.